The arrival of autumn in Ireland has always been more than just a change in season; it marks a time of abundance, gratitude, and preparation for the long, dark winter ahead. In ancient times, the Irish harvest was celebrated through festivals that combined Celtic fall traditions with later Christian observances like Michaelmas. These gatherings were filled with feasts, storytelling, rituals, and symbolic practices that blended the mystical with the practical. Today, echoes of these celebrations remain in Irish culture, offering a glimpse into a way of life deeply tied to the land and its cycles.

The Meaning of the Irish Harvest

The Irish harvest was central to survival. Grains, vegetables, and fruits gathered during autumn determined whether a family or community would thrive through the winter. Traditionally, harvest time began after Lughnasadh in August and extended through September, culminating in feasts such as Michaelmas at the end of the month.

The harvest wasn’t just about food; it symbolized balance. It was a time to honor the Celtic fall traditions that celebrated the bounty of the earth, while also acknowledging the waning light as days grew shorter. Fields were cleared, animals were slaughtered for meat, and thanks were given to gods, saints, and spirits alike.

Michaelmas – The Feast of St. Michael

Christian and Celtic Blending

Michaelmas, held on September 29, honored St. Michael the Archangel, the protector against evil and the harvester of souls. When Christianity spread through Ireland, this feast merged with older Celtic harvest rituals. It marked the turning point of the farming year when debts were settled, workers were paid, and contracts renewed.

Michaelmas Goose and Other Foods

One of the most famous Michaelmas traditions in Ireland was the eating of the Michaelmas goose. Families who could afford it would roast a fattened goose, often served with apples and potatoes. Goose fat was also said to protect against illness during the cold months ahead.

Other staples included:

- Colcannon (mashed potatoes with cabbage or kale)

- Barmbrack (fruit bread linked with divination)

- Apples from the autumn harvest

- Blackberries, which folklore warned should not be picked after Michaelmas, as the devil was said to spit on them.

Folklore and Superstitions of Michaelmas

- Protecting Health: Eating goose on Michaelmas was believed to ensure good health for the coming year.

- Weather Predictions: Farmers watched Michaelmas weather closely, believing it forecasted winter conditions.

- Blackberry Superstition: A widely held Irish belief held that after Michaelmas, blackberries were spoiled because the devil had cursed them.

Celtic Fall Traditions and Festivals

Long before St. Michael, the Irish honored the harvest with their own rituals. Celtic fall traditions reflected the sacred connection between the natural world and the divine.

Lughnasadh’s Influence

Though primarily celebrated in August, Lughnasadh set the stage for the harvest season. It was dedicated to Lugh, the god of skill and craftsmanship, and featured first-fruit offerings, athletic games, and matchmaking. By Michaelmas, these celebrations shifted to a more solemn recognition of the waning sun and the need for preservation.

Samhain Approaches

Michaelmas was not the end of harvest festivals; it was a bridge to Samhain in late October, when the last of the crops were gathered, and the Celtic new year began. Samhain carried a more spiritual and supernatural weight, while Michaelmas focused on the practical balance of food, contracts, and protection.

Rituals and Customs of the Irish Harvest

The Irish harvest wasn’t only about food and feasts. Customs carried deep symbolic meaning:

- The Last Sheaf: Farmers often saved the last sheaf of wheat as a charm for good luck. Sometimes it was woven into a Corn Dolly, representing fertility and protection.

- Bonfires: Leftover from pagan traditions, fires were lit to honor the sun’s power as it faded.

- Divination Games: Young people used harvest foods like apples and barmbrack to predict their future, especially in matters of love and marriage.

- Offerings of Thanks: Small gifts of grain or bread were left at sacred wells and stones to appease spirits and ensure blessings.

Michaelmas in Irish History

During medieval times, Michaelmas was one of the “quarter days” when rents were due, servants were hired, and fairs were held. It wasn’t only a religious feast but an economic and social anchor point. Entire villages came together for fairs featuring music, horse trading, storytelling, and dancing.

These fairs carried on traditions from Celtic gatherings like the Aonach, where clans met to celebrate, settle disputes, and arrange marriages. By blending Christian rituals with older Celtic customs, Michaelmas became a truly Irish hybrid celebration.

Symbols of Michaelmas and Celtic Autumn

The Goose

A symbol of protection, sustenance, and foresight.

Blackberries and Apples

Linked to fertility, temptation, and divine blessings.

The Sheaf or Corn Dolly

Representative of the harvest spirit and carried forward into the next planting season.

St. Michael the Archangel

Protector and warrior, blending Christian ideals with Celtic warrior traditions.

How Irish Harvest Traditions Live On Today

While the large-scale harvest feasts of old are no longer central to Irish life, many customs endure:

- Families still bake barmbrack around late September and October.

- Irish festivals in towns and villages honor local harvests with food fairs.

- Michaelmas remains a date of cultural memory, often tied to agricultural events.

- Folklore, such as the “devil spoiling blackberries,” is still retold in rural areas.

Even in modern celebrations like the National Ploughing Championships, echoes of ancient Celtic fall traditions remain in Ireland’s connection to the land and its cycles.

Celtic Jewelry Inspired by Autumn Festivals

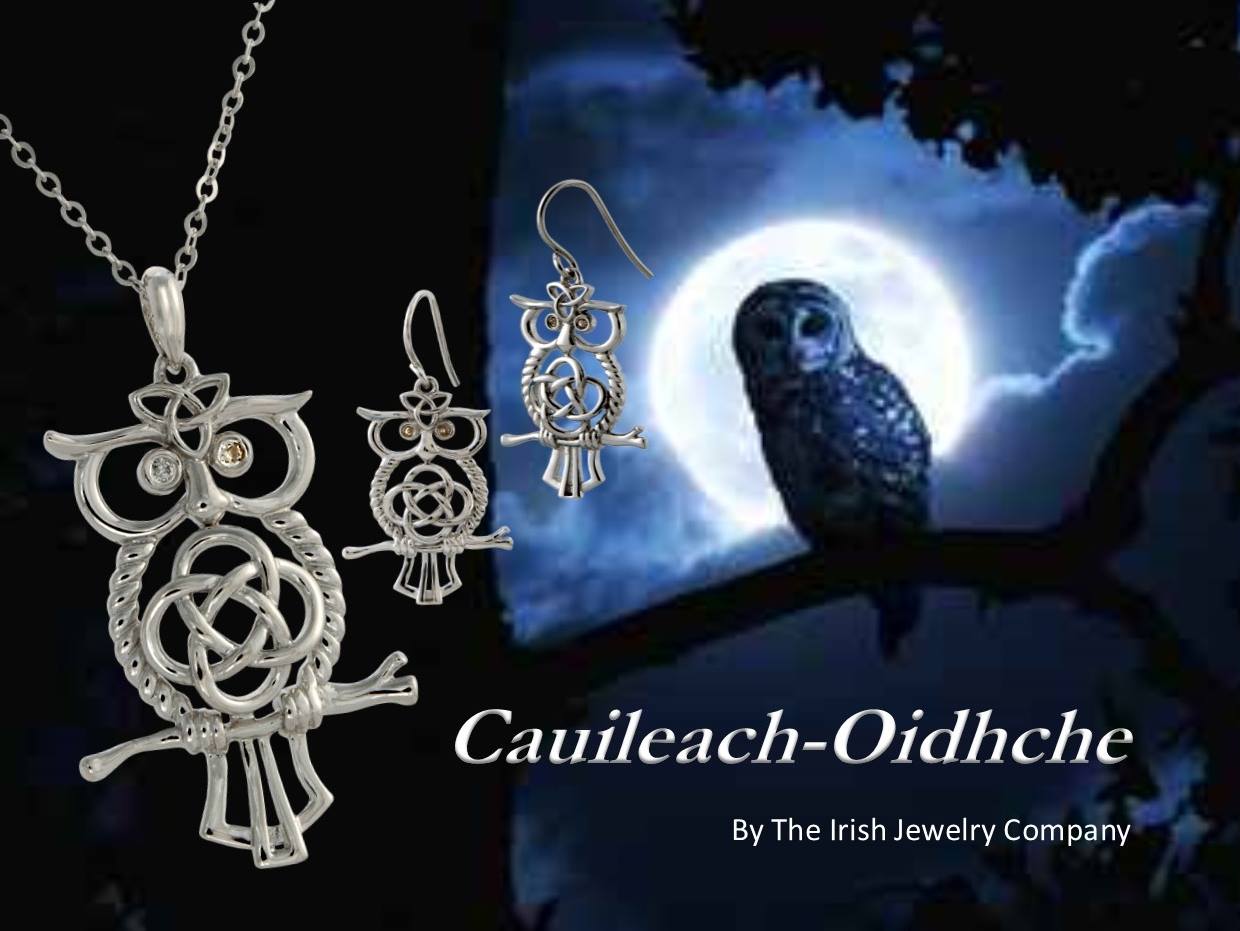

Harvest rituals often included wearing or gifting symbolic jewelry. Celtic knots, sheaves of wheat, and protective talismans were linked to abundance and protection. Today, jewelry inspired by Celtic fall traditions continues to carry these meanings.

Pieces like the Celtic Knot Jewelry serve as modern reminders of ancient cycles of life, death, and renewal. Just as harvests ensured survival, jewelry celebrates endurance and continuity in Irish heritage.

Conclusion

The Irish harvest season, with Michaelmas at its center, reflects Ireland’s ability to weave together the practical and the mystical. From Celtic fall traditions rooted in the land to Christian overlays honoring saints, the autumn feasts of Ireland highlight gratitude, community, and resilience.

Today, these customs endure in folklore, food, and symbolic practices, reminding us to pause, give thanks, and honor both the abundance and impermanence of life. Whether through baking barmbrack, enjoying a Michaelmas goose, or wearing Celtic jewelry with harvest symbolism, these traditions keep Ireland’s rich cultural heritage alive.

During the eighth century the Catholic Church designated the first day of November as ‘All Saints Day’ (‘All Hallows’) – a day of commemoration for those Saints that did not have a specific day of remembrance. The night before was known as ‘All Hallows Eve’ which, over time, became known as Halloween.

During the eighth century the Catholic Church designated the first day of November as ‘All Saints Day’ (‘All Hallows’) – a day of commemoration for those Saints that did not have a specific day of remembrance. The night before was known as ‘All Hallows Eve’ which, over time, became known as Halloween.